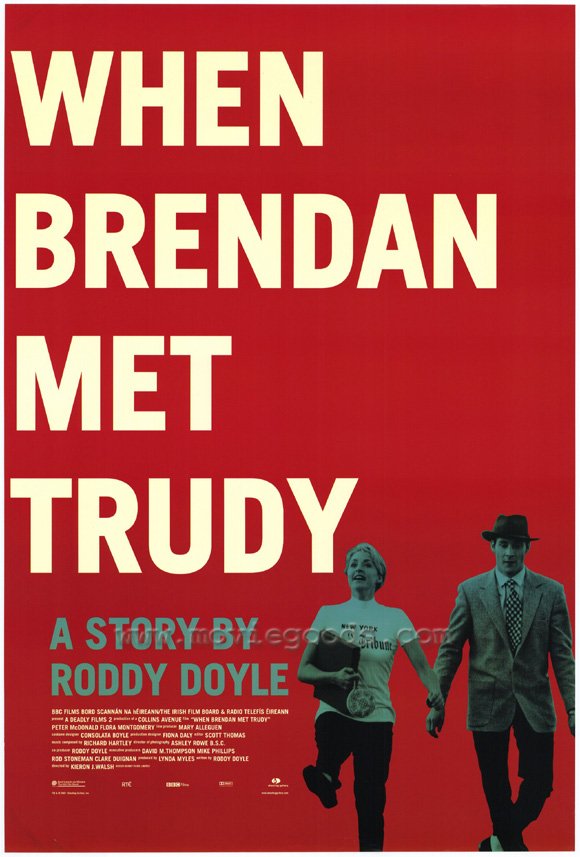

When Brendan Met Trudy is a 2000 Irish film and very much a

product of the Celtic Tiger, an anything-can-happen mess of a movie that plays

with everything from conventional characterization to genre, perspective and

homage.

When Brendan Met Trudy is a 2000 Irish film and very much a

product of the Celtic Tiger, an anything-can-happen mess of a movie that plays

with everything from conventional characterization to genre, perspective and

homage.

Brendan (Peter MacDonald of I Went Down and Nora) is a Godard-loving schoolteacher and choir singer. He

is uptight, reserved and shy. Nothing seems to interest him very much and he

has reverted so far into his shell that even casual situations involving other

people become embarrassing disasters. He meets Trudy (Flora Montgomery of Goldfish Memory) in a pub and their

instant attraction changes Brendan forever.

Director Kieron J Walsh (this year's Jump) and writer Roddy Doyle (whose

screenplay credits also includes the adaptations of his ‘Barrytown Trilogy’ – The Commitments, The Snapper and The Van)

have fashioned a freewheeling and genre-bending romcom that is as much a love

letter to cinema as it is a story about Brendan and Trudy. As a result, it is a

mess. First of all, the film is without a clear narrative line. A strange

subplot that threatens to throw the whole film in a more Suspicion-like

direction is dispensed with almost as quickly as it is introduced. Worse still

is a subplot about an African prince, one that is totally out of place.

Similarly, Brendan is far from a carefully thought out character. He seems to

climb in and out of his shell whenever the story requires him to. Worse off,

however, is Montgomery, saddled with a character that flips from the

movie-typical kooky and energetic city girl to psycho killer to burglar to

begrudging and vulnerable innocent. You never really get a sense that Trudy

cares all that much about Brendan, so much so that you watch the film and wait

for the story to take a dark turn, like the wholly predictable An Education.

Brendan and Trudy do not go through any real change (let’s ignore that silly

word ‘arc’), as they remain as indefinable and unknowable as they did at the

beginning. As a result, the film is fairly incomprehensible and inconclusive,

albeit light and often fun.

The film captures a time and place, powered as it is by the same

feelings of excitement and prosperity that imbued Celtic Tiger Ireland. Because

anything could apparently happen in Ireland then, the film frequently jumps

into Godard homage with a comedic recreation of the famed Champs d’Elysses

scene from A bout de soufflé. Walsh takes the excitement of the French

New Wave and creates an Irish film that is somewhat rare, one that is actually

happy to be Irish – not unlike Gerard Stembridge’s Rashomon-esque About Adam from the same year.

Staying with the Godard strain within the film, the film is ultimately an

exercise in cinematic style, one that thanks Godard for breaking the rules

without considering what he broke them for. Like early Tarantino, it is style

for style’s sake. Problematically, the film has very little to say.

Watching it now, with Ireland back in the grips of a bad economy, the

film seems so naively optimistic. It becomes lovable in its obsolescence and

touch bittersweet. However, that said, the film can be a lot of fun, with even

the abandoned Suspicion subplot rewarding patience with a very good,

though belated, punch line. It is a mess and it goes absolutely nowhere, it is

a funny and endearing trip.

No comments:

Post a Comment