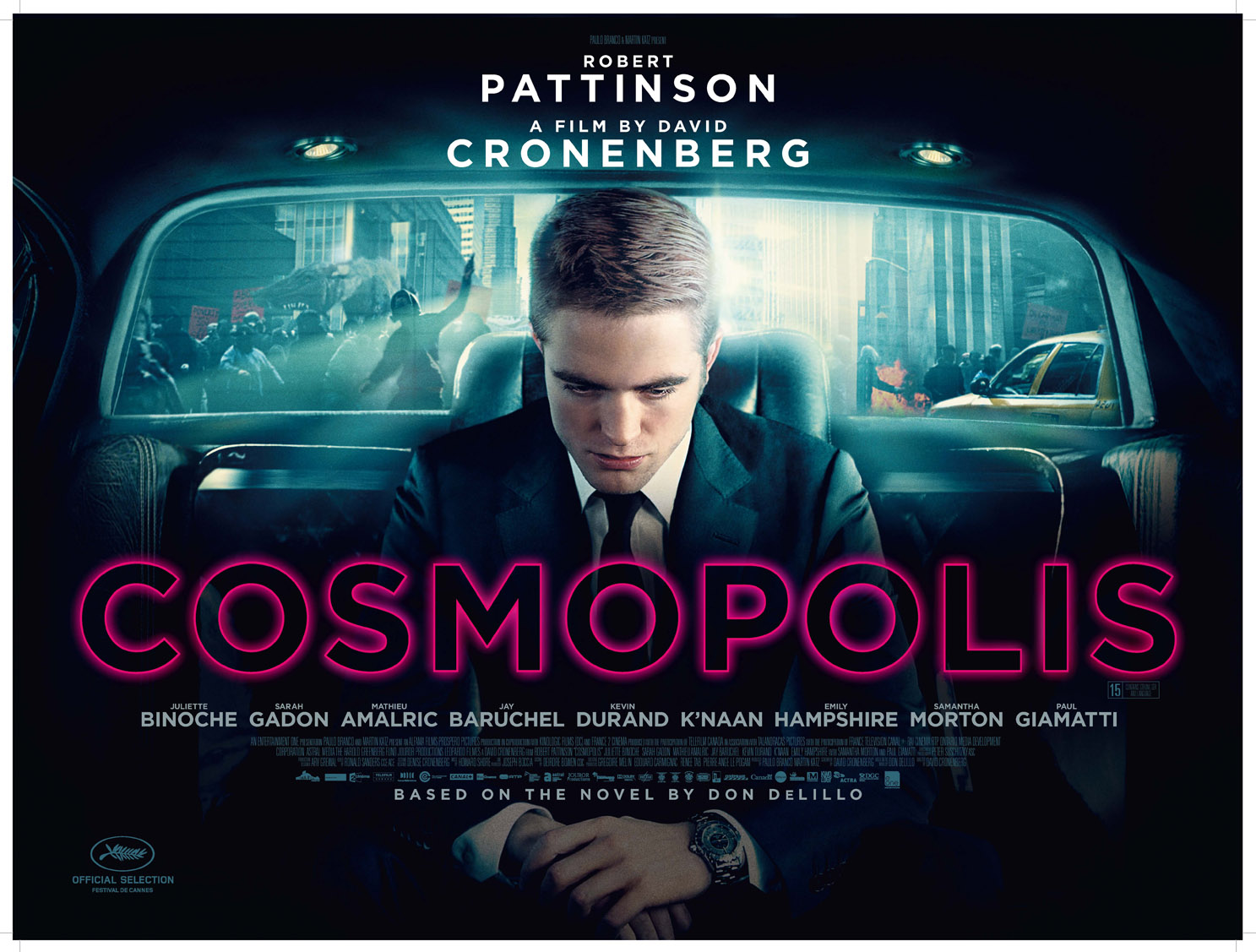

Eric Packer (Robert Pattinson, doing rather well despite being cast presumably only for marquee value) is a young billionaire who has everything he wants. He jumps into his cork-lined and impenetrable limousine and travels through the city in search of a haircut. On the way, he has one-on-one meeting with a variety of advisors, their talks becoming increasingly philosophical. He also meets his new wife Elise Shiffrin (Sarah Gadon) for a variety of meals, their relationship unconsummated and stalled. He also meets Benno Levin (Paul Giamatti), a disgruntled ex-employee who is dedicated to killing Packer in order to give his life meaning.

Like Cronenberg’s previous, A Dangerous Method, the film is primarily a talking piece. Cronenberg has lately become committed to the idea that film need not especially be a visual medium and that images of people talking are of equal import. The conversations in Cosmopolis are stilted and deeply intellectual, taken largely from Don DeLillo’s original 2003 novel – which now seems remarkably prescient in view of the subsequent economic collapse. The film contains a philosophical and economic critique of the modern world in which young billionaires have two elevators, which they choose between depending on their mood and everyone keeps an eye on the rises and falls in the stock market like more spiritually-minded people would keep an eye on tea leaves. The intellectual conversations range from the fascinating to the almost incomprehensible, delivered with a palpable coldness and near total insincerity. His theory coach, Vija Kinski (Samantha Morton) trains him on philosophical matters, pointing out that money has become so abstract that “it talks to itself”, and, hence, people are almost obsolete. She criticizes a society fascinated by wealth, but she does not seem to be bothered by it all that much, her intellectual talk becoming exactly that. That Packer might slowly be returning back to humanity is reflected in how he becomes increasingly dissatisfied with other peoples’ inane conversations.

The film is about a world in crisis, on the brink of economic ruin but with no alternative and no place to go. Even the protesters are ineffectual with one particularly destructive and anarchic riot quickly cleaned up and forgotten. Even the famous André Petrescu (Mathieu Amalric, delivering one of the film’s few funny performances), an anarchist prankster, acts for his own camera crew, but does not have any valid point to make. The view of the world from inside Packer’s sound-proofed limousine seems faraway and unreachable, the life outside moving in a graceless silence as if it is all playing from a television on mute. If Packer is getting tired of his lot, the film makes clear that there is little else for him to do. Though unreachable, however, the world outside feels remarkably and horridly familiar as it clearly refers to the economic collapse and the Occupy movement, even to the notorious incidence of the self-immolation of the Vietnamese monks. Unlike Crash, it becomes increasingly clear that Cosmopolis is about our world and not necessarily some post-human future.

The film is a hard film to like, ultimately because there are none of the typical pleasures associated with escapist cinema nor are there any clear-cut messages or arthouse gimmicks. Cosmopolis is a very esoteric and somewhat unique film, which is difficult to categorize and even harder to qualitatively appraise.

However, the film does reach a fascinating and rather moving climax, with an extended conversation between Packer and the Mark Chapman-like Levin, introduced with Levin actually saying, “Let’s sit and philosophise together.” Silly as that may sound, the film develops into a conversation about finding meaning in one’s life and gaining the ability to feel again. Giamatti gives the film its sole believable and human performance, capturing with great honesty and subtlety a man who has nothing and who no longer knows himself. It all sounds very arch, but in the context of the rest of the film, coming as it does at the end, it works very well. The arthouse prerequisite ambiguous ending notwithstanding, Cosmopolis does develop into something much more thought-provoking and, surprisingly, moving, something more than the rest of this very strange and very cold film. It feels almost triumphant in a weird and incalculable way.

No comments:

Post a Comment