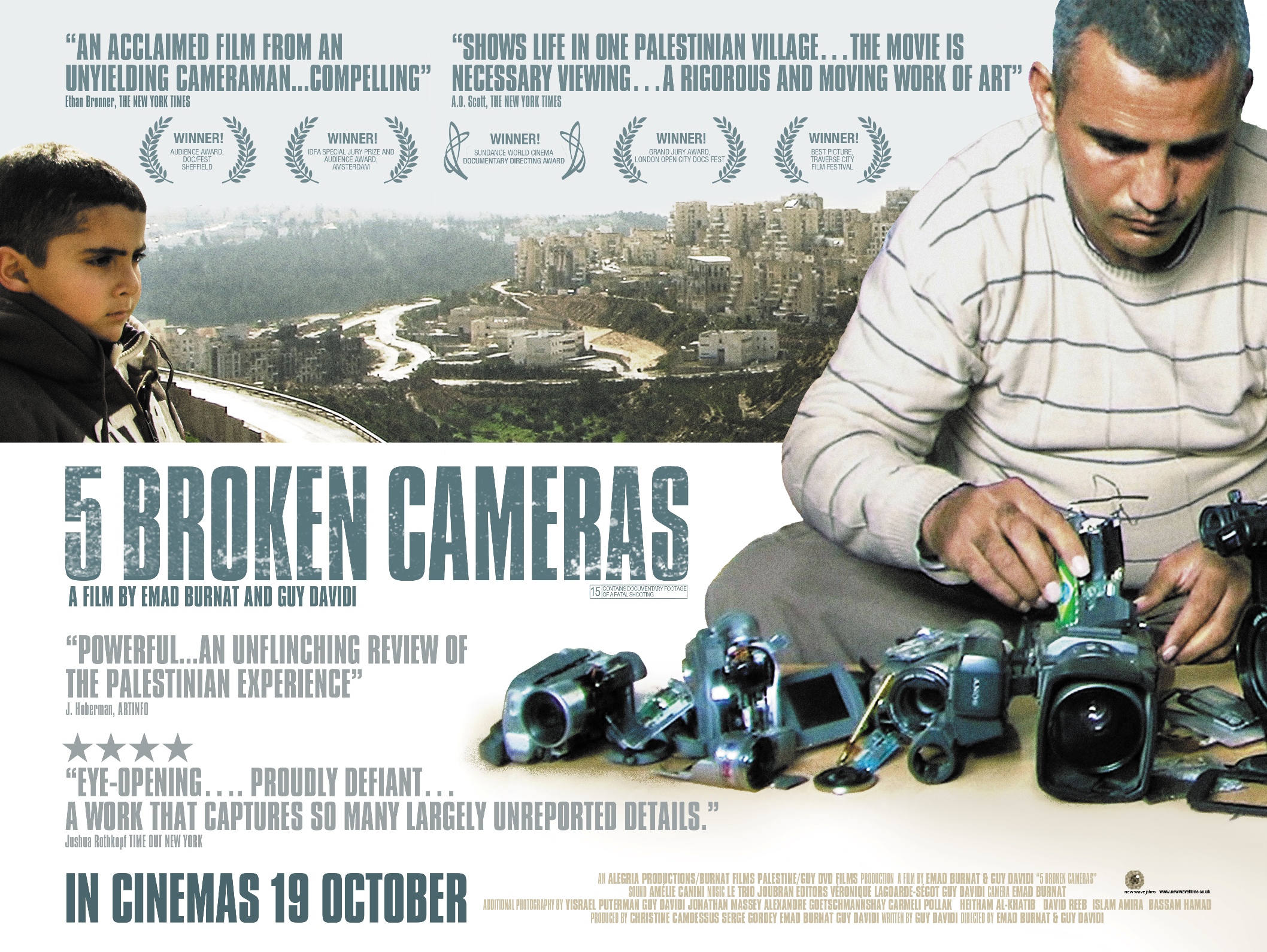

Five Broken Cameras is a documentary about the people of Bil’in, a small town in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, and their rebellion against the building of a separation wall that cuts them off from half of their farming land. Shot primarily by a Bil’in resident, Emad Burnat, who is also co-director and co-producer, the film is a remarkably pacifist look at resistance against oppression.

Filmed with six different cameras, the film charts the beginning of the resistance to the wall and the developing Jewish settlement of Modi’in Ilit in the West Bank between the years 2005 and 2010. The film also reveals how five of Burnat’s cameras were destroyed in the process of filming the resistance, often by bullets. Burnat also documents the first five years of the life of his fourth son, Gibreel, born on the day that the Jewish bulldozers moved into the town’s land.

As a testament to passive resistance, the film is surprisingly moving and a good introduction to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict for those who find it either too complicated or too hopeless. Instead of militarism, what Burnat’s film and the people of Bil’in represent is a grassroots campaign of resistance, which is about peace and co-existence and mutual respect, as opposed to Intifada and mass killings. Although the film is not primarily about the past, the building of a Jewish settlement on Bil’in land being an immediate and present-day problem, it does not deny the past. Burnat’s four sons reflect the past surprisingly well, with the first son born in a time of hope following the Oslo Peace Accords, the second three years later at a time of uncertainty after Oslo proved to have little effect if not to be entirely detrimental, the third son on the very day that the Second Intifada began. Gibreel, born on the day that the Jewish bulldozers arrived, ages tellingly over the course of the film, with ‘cartridge’ and ‘army’ being some of his first words. The sordid history of the conflict infects his childhood, robbing him of innocence much too soon. Hence, though the resistance is a just one, the film is also aware that there are always real complications. Towards the end, in a sequence that feels staged but no less effective, Gibreel will ask his father why he shouldn’t just kill Israeli soldiers.

The film is close to propaganda, especially in the editing and the addition of a post hoc voiceover, but its message is ultimately one of peace. The Bil’in movement begins as a small local effort but expands over the course of the film to an almost international movement, which also includes a mix of Westerners and Israeli activists. Burnat does not refuse to show the complexity of a movement that is more than merely an Israeli versus Palestinian one. In fact, the film was co-financed by Israel. And though the film paints the Israelis as the perpetrators and the oppressors with the force of propaganda, it is hardly manipulative as the facts remains damning enough. Again, towards the end, the film becomes more staged with celebratory images of his children at the seaside for the first time in some of their lives, but it is the film’s truth that bares it out. In fact, one of the sequences that push the film closest to the melodramatic clichés of Hollywood is horribly all too real. Ultimately, the film has an emotional force and a political resonance that recalls some of the late Edward W. Said’s writings on the subject, which advocate passive resistance, co-existence and understanding.

As an introduction to the conflict, the film is certainly useful because it does not show the too familiar Middle East of Western media. It is not a film of angry militarism and violence, but one of justifiable outrage, bravery and dedication. The film introduces some of the citizens of Bil’in, particularly Adeeb and Bassem, or “El-Phil” – The Elephant – as the town’s children affectionately call him, both outspoken and politically charged but also both entirely likable. The film has a remarkably human feel to it, despite all the politics and resistance. It becomes not so much a film about a particular grievance, but more a portrait of a small community’s resistance to a large invasive and faceless occupier, a classic American underdog story and not a million miles away from the recent Irish resistance documentary The Pipe. One sequence, in which Burnat is under house arrest recalls the brilliant This Is Not A Film. The film is also often very funny, with a strange sequence in which the villagers are amused by some chickens that are climbing a tree for no apparent reason. Adeeb’s rationale for the behaviour is “They have their freedom.” They are climbing the tree because they can, nothing is stopping them, a sentiment which speaks more for the film’s sense of the importance of freedom and self-determination than for its politics.

Though it cannot help but be politically charged, Five Broken Cameras is ultimately a film about the resistance of villagers to the unlawful seizure of their land. It represents the resistance, and the broader conflict, in human terms first and foremost, refusing to allow rhetoric to muddy the waters in what is essentially a story of justifiable anguish at an excessive occupation. As with Said’s work, it is critical of more than just the Israelis, also taking a jab at the Palestinian Authority. As the years and the film progress, Burnat and his co-director Guy Davidi, become filmmakers, but it is during their more amateurish and rough-edged moments that a certain type of immediacy and power shines through.

No comments:

Post a Comment