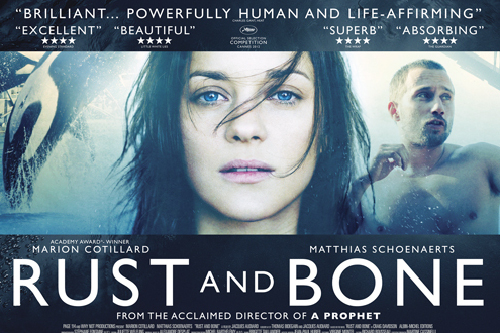

Rust and Bone is the sixth feature from writer-director Jacques Audiard, best known for his previous, the tough A Prophet. Rust and Bone feels like a return to the odd couple motif that gave his otherwise gritty 2001 crime film Read My Lips a heart. Whereas these previous two enlivened the tropes of the crime film through their extreme intensity and earthy realism, Rust and Bone is a bit of a departure, being mainly a romance between a disabled woman (Marion Cotillard) and a bare-knuckle boxer (Matthias Schoenaerts).

Unexpectedly put in charge of his young son Sam (Armand Verdure) after his mother disappears, the practically destitute Alain (Schoenaerts) moves to Antibes and begins to look for work. As a bouncer in a nightclub, he meets Stéphanie (Cotillard), a killer whale trainer. Following a horrible accident at her work, Stéphanie is disabled and a friendship develops between her and Alain. Meanwhile, Alain gets involved in bare-knuckle boxing for some quick cash.

Like Read My Lips and A Prophet, there is nothing especially new here in terms of the film’s plot, which is instead somewhat derivative. However, where the film excels is in Audiard’s ability to give potentially tired material a breath of fresh air. With a handheld camera and natural lighting, his films approach the material with an eye for realism and an honesty of focus. Though it can be manipulative, Rust and Bone is refreshingly uncritical and its emphasis on the emotions of the characters rather than on the developing plot mechanisms makes it surprisingly warm and heartfelt. Technically, the film rarely displays any meaningless stylistics, with Audiard typically preferring to shoot his characters in tight close-ups even when mobile. The film is not without its technical flourishes but, for the most part, the film stays with its characters and happily down to earth. As a result, the film’s contrivances become believable and Rust and Bone becomes a film that it is very easy to be taken away by.

Audiard is ably assisted here by some fantastic cinematography. Stéphane Fontaine, in his third collaboration with Audiard, proves equally adept at shooting intimate indoor scenes with a minimum of intrusive lighting set-ups and the large crowds scenes set in the sea park. Similarly, the film has many impressive lyrical sequences usually to do with the killer whales or with the bare-knuckle boxing, which are off-putting in terms of the film’s otherwise realist aesthetic but do manage to convey a certain beauty. The scenes early in the film set in the sea park are almost sickeningly tense as we are left waiting for something horrible to happen without being quite sure how or when. When the accident does occur, it is shocking precisely because it is unexpected, unseen and subtly presented. Similarly, the bare-knuckle boxing sequences are all horribly realistic, despite a few passages during which the film seems to poetise the violence.

However, the film is best during its slower and quieter moments between Cotillard and Schoenaerts and it is here that the performances get the chance to shine. They approach their characters with a large amount of understanding, often conveying a lot without saying very much. Similarly, they are far from one-note and both display moments of real cruelty, which the film bravely does not make apologies for, instead accepting that, in real life, there are never simply just heroes, villains and victims. Cotillard makes Stéphanie’s devastation queasily real but is also powerfully convincing as a woman tries to get herself back up after a life-shattering accident. One sequence in which Stéphanie begins to do her whale-training exercises for the first time since the accident is a moving and triumphant moment, only slightly sullied by Audiard’s bizarre decision to drown it out with Katy Perry song on the soundtrack. Schoenaerts is equally good in an intensely physical performance although, again, he is best when things are quiet. We are not always supposed to like him, but Schoenaerts is adept at portraying a hint of vulnerability even when he is at his most thuggish. His developing attraction to Stéphanie is well handled and his refusal to let her sit inside and mourn her legs could have been annoying and contrived but is instead surprisingly convincing. It is a tribute to the two lead actors that when the film is focused on them it is at its best.

The film is not without its flaws, often the result of a certain over-egging of the cake. Audiard sometimes moves into an oddly lyrical approach during the bare-knuckle boxing scenes, which feels like a bit of a misstep. The same is true for the use of Katy Perry during an emotionally significant moment that would have worked better without brash American pop. Similarly, the film’s final third does become less convincing and towards the end the film rushes to throw a variety of dramatic devices into the mix, none of which really come off. Cotillard is robbed of a real ending and Schoenaerts is given too many. One involving a frozen lake, while admittedly effective as it plays out, feels in retrospective to be a little too artificial and cheap. The ending also feels a little too optimistic, as everything seems to work out so well that it undercuts the film’s realism somewhat. However, the film is full of enough nice touches and enough honesty that these inconsistencies feel like quibbles.

Rust and Bone is a very good drama, marked by Audiard’s typical intensity and his ability to make recognisable material refreshingly new. Cotillard and Schoenaerts compliment Audiard’s directness with great performances, most likely a career best for both of them. The film is hardly perfect but is not an easy one to dismiss.

No comments:

Post a Comment