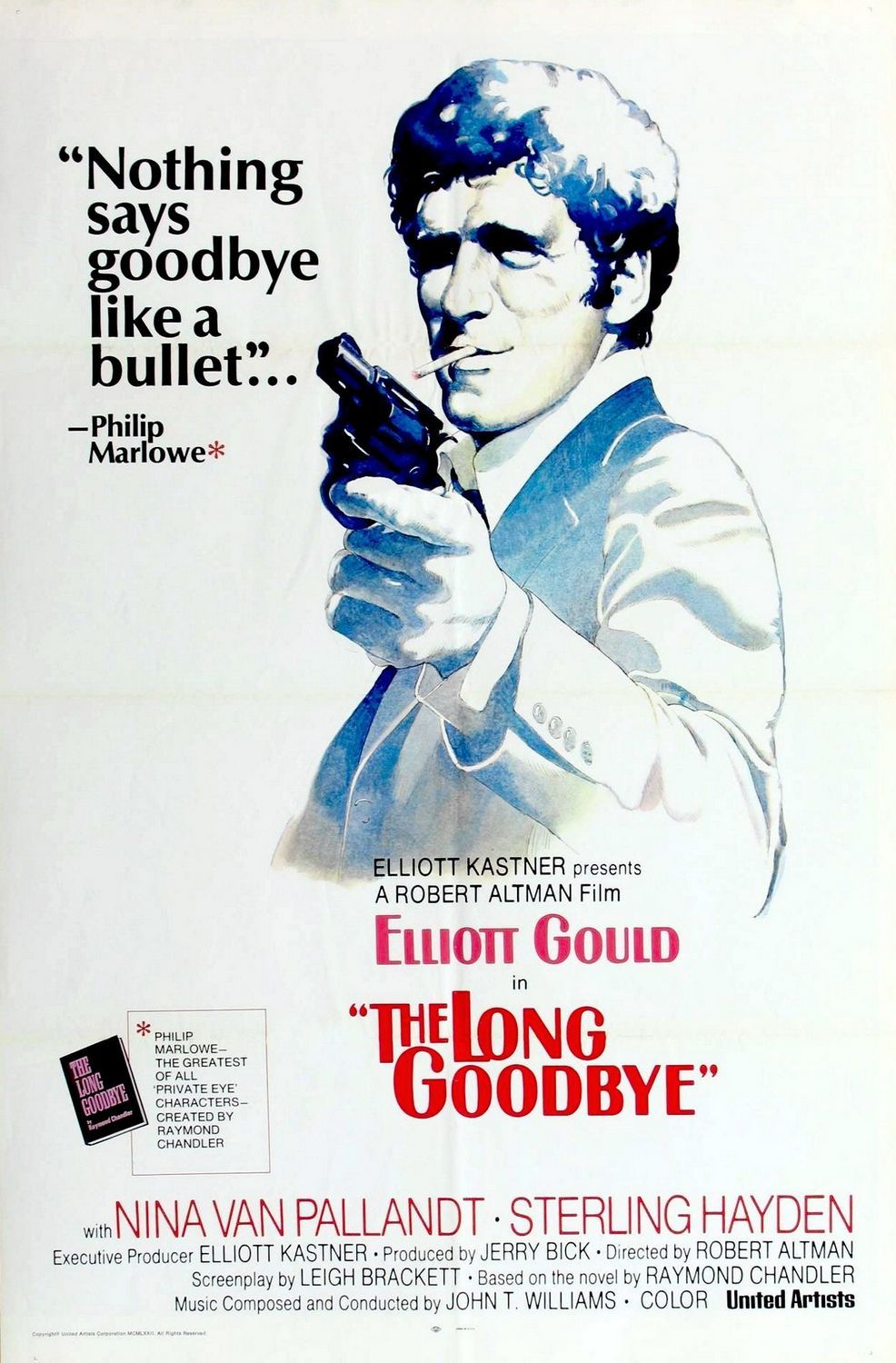

Robert Altman’s odd, modern and

much misunderstood The Long Goodbye has been getting a lot of attention

lately, presumably because of a re-release on DVD and Blu-ray, which got me

wondering, “Is it not only the best adaptation of a Raymond Chandler novel, but

one of the greatest films ever made?”

Anyone familiar with the film

will know that the typically convoluted Chandleresque plotting – already toned

down in a book that is much more melancholy and bleak than usual – will get

little attention in Altman’s film. Suffice it to say that Philip Marlowe

(Elliot Gould) is engaged by his friend Terry Lennox (Jim Bouton) to drive him

to Mexico. Marlowe does this and is immediately arrested for aiding and

abetting a murder, as it seems Terry has murdered his wife. Marlowe is

committed to clearing Lennox’s name and, by extension, his own, which leads him

into contact with Roger and Eileen Wades (Nina van Pallandt and Sterling

Hayden), neighbours of the Lennoxs’, and a crazed gangster Marty Augustine

(Mark Rydell) who thinks Marlowe owes him money.

The Long Goodbye was not a

success on its first release, with many Chandler fans apparently outraged by

what they saw as Altman’s contempt for the genre and for Chandler’s character

and stories. Many complained that Gould portrayed Marlowe as a dimwit, a

know-nothing chancer who blunders his way through the case before it gets

wrapped up for him. However, this is not entirely fair, since the source novel

– one of Chandler’s last completed Marlowe novels – portrays a Marlowe who is

older, sadder and who takes longer than normal to solve a simpler case (it is

by far the longest Marlowe novel). Indeed, Altman’s film is much more faithful

than most other Chandler adaptations, if not in plot particularly then at least

in terms of tone. The novel of ‘The Big Sleep’, for instance, is not nearly as

happy go lucky as Howard Hawks’ celebrated film.

As a brief side note, the novel

‘The Long Goodbye’ might just be Chandler’s best too. If ‘The Big Sleep’

represents a stylistic perfection, the epitome of the hard-boiled crime story

or at least Chandler’s take on it, then ‘The Long Goodbye’ represents a bold

and fascinating experimentalism. ‘The Long Goodbye’ is long and wandering and

far from flawless, but it does suggest a master of the form trying to innovate,

trying out new themes and styles, making ‘The Long Goodbye’ a fascinating blend

of risks that fail and risks that pay off. Whether stylistic perfection or

stylistic experimentation is ultimately preferable ought to be the subject of

another article, but, as far as ‘The Long Goodbye’ goes, who better to adapt it

than the master of uneven, purposefully slapdash and experimental cinema,

Robert Altman.

Altman’s film is a crime film –

of course it is, and it is full of character and confrontations and incidents.

However, these scenes are injected with a nervous energy and an unpredictable

reality and they often don’t make a whole lot of sense, reflecting reality,

which hardly follows a carefully planned narrative line. By bringing melancholy

and disillusionment to his novel, Chandler was trying to bring more realism to

his stories than he had before. Altman takes this melancholy and adds a vague,

loose and inconclusive narrative, imbuing The Long Goodbye with much

more realism than would be expected from a Marlowe story. Think of the opening

credits sequence, which is not the beginning of a crime film at all, wherein

Marlowe bums around his flat trying to feed his cat (clearly put out by it but

it is obviously the only constant friend he’s got so he lets it bother him). He

goes out to the store to buy some cat food and Altman intercuts between Marlowe

driving through LA at night and Lennox driving around. Neither seem to know

particularly what they are doing and neither seems to be going anywhere in

particular. Coupled with an incredibly adaptable John Williams score, it

manages to be extremely sad.

This opening represents perfectly

that Marlowe is not a bungler, that he is a lonely man cast adrift in an

unwelcoming world that is as meaningless as it is corrupt. Marlowe’s defence

mechanism for all of this is the catchphrase “It’s alright with me”, which he

says whenever something throws him or confuses him. This stoicism is rarely

lifted, but every now and then something truly awful happens that forces

Marlowe to try. His other defence mechanism is the wit that Chandler’s Marlowe

had. Chandler’s Marlowe always knew how to get out of a tight scrap and he

always had a good one-liner for any situation. Altman’s Marlowe tries to be

witty but is often ignored or interrupted. Too often we see Marlowe trapped and

unable to escape and all that is left for him to do is go nuts. Twice in the

film (at least) he is so angry that he is almost speechless. Following his stay

in prison and immediately following Roger Wade’s suicide – here in particular –

he can barely string sentences together.

In keeping with his old-fashioned

stoicism and sense of humour, the only guy that Marlowe seems to immediately

understand is the Wade’s odd gatekeeper (Ken Sansom) who only allows people

through if they can name the golden age Hollywood star that he is imitating.

Marlowe’s other friend, Lennox, is the only other character able to play along

with this gatekeeper. Equally old-fashioned, Marlowe has a sense of morality, one

that is ultimately a danger to him as he is susceptible to the plots and tricks

of the people that he likes. The reason he cannot see the truth about Terry

Lennox and Eileen Wade despite so much evidence is, ultimately, because he

trusts them. He believes in them, just like he believes in morals and, as

Altman makes clear, in 1970s LA morals are almost a character flaw.

The only characters who seem to

have any control are those who have left any kind of morality behind –

Augustine smashes a Coke bottle on his girlfriend’s face (Jo Ann Brody) despite

being in love with her to make a point and Dr. Verringer (Henry Gibson) is

almost supernatural in his ability to get people to do what he wants. Verringer

slaps a wild and angry Roger Wade in the face and somehow calms him down. Both

Augustine and Verringer’s victims wander through the rest of the film like

ghosts, the facial violence seemingly removing their last vestige of humanity.

In other words, they give up trying to take something good out of the world. Like

all of Verringer’s patients in his clinic, they are no longer there. Terry

Lennox becomes immoral, which is why Altman focuses on him during that

melancholic opening. Driving away from home, where his wife lies dead (beaten

to death – one cop tells Marlowe to look at what Terry did to her face), shaky

and frightened, Terry symbolically puts on his driving gloves to cover up the

scars on his fists and, with that, covering up his humanity.

Starting and ending with the tune

‘Hooray for Hollywood’ by Johnnie Davis (the only music that isn’t a variation

on William’s score), The Long Goodbye does not represent Altman’s

contempt for a genre. It merely recognises that Hollywood is an escape, an

unreality, and one that may be a danger if used as a way of life. Hence,

Marlowe’s wit fails and his naiveté (read his faith in other people) puts him

through all manner of unpleasantness. Indeed, Minnie’s exasperation with

Hollywood (“They set you up to believe in everything”) in Cassavetes’ Minnie

and Moskowitz could be Marlowe’s own.

However, this is turned on its

head in a surprise ending in which Marlowe guns down Terry in Mexico and

dancing off into the sunset – in an ending that quotes The Third Man.

Terry has been declared legally dead and so one believes that Marlowe is safe

from prosecution. Not only that but despite everything cruel and wrong about

the world, Marlowe ultimately gives the villain his comeuppance and is safe

from the law by a contrivance worthy of Hollywood. Hollywood saves the day and

everything Marlowe was standing by is oddly reaffirmed, the very thing that

some many supposed Altman to be contemptuous of is celebrated. In other words,

hooray for Hollywood. Or, to quote:

Hooray for Hollywood

That screwy, ballyhooey Hollywood

Where any office boy or young mechanic

Can be a panic, with just a goodlooking pan

Where any barmaid can be a star maid

If she dances with or without a fan

Hooray for Hollywood

Where you're terrific, if you're even good

Where anyone at all from TV's Lassie

To Monroe's chassis is equally understood

Go out and try your luck, you might be Donald Duck

Hooray for Hollywood

All of this and I haven’t even

mentioned Altman’s directing, his use of non-professional actors, his use of

improvisation, his sound mixing and editing. The Long Goodbye is great

for all of the reasons above, but it is the Robert Altman touches that make it

endlessly rewatchable and, for me, one of the greatest films ever made. In the

book, the alcoholic Roger Wade was Chandler’s self-portrait, one of the experiments

that paid dividends since it gave the book’s melancholia a personal touch.

Sterling Hayden was an alcoholic and was apparently wracked by guilt for naming

names before HUAC in the 1950s. In the film, Altman allows Hayden to give full

vent to his own demons, allowing for an incredible performance full of pain and

truth as well as a sense of humour. Altman keeps the camera distant. All the

actors are miked up and the camera gets close by zooms alone and the sound is

mixed (brilliantly) later. As a result, the actors had total freedom to walk

and talk. Hayden inhabits his house, smashing around the set and talking

gibberish without a concern for blocking and the camera and the sound, making

it all feel so spontaneous and out of control and real. Like Cassavetes, Altman

manages to capture the chaos and unpredictability of everyday real life, making

his films full of incident and observation. The improvisation only adds more

insight as each actor brings more perspective to their characters than a single

writer can. In other words, the film is alive.

Hopefully, I have been successful

in my bid to convince that this film deserves wide acclaim and recognition. I

didn’t initially like The Long Goodbye, I didn’t get it, and it wasn’t

until I saw it for the fourth time in about a year that I realized why I was so

constantly drawn to it. For me, it is a masterpiece, a classic 1970s film of

risk and invention, sadness and humour and one of Altman’s greatest

achievements.*

*The others for the record, are MASH, California

Split, Nashville, Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull’s

History Lesson and A Wedding.

See also:

No comments:

Post a Comment