One of the categories that might define ‘great art’ may well be that the work cannot be adapted into another medium without losing that which makes it great. For example, A Woman Under The Influence would lose the raw immediacy and tenderness of Cassavetes’ camera, Jeux Interdits would severely miss the remarkable expressiveness of the then five-year old Brigitte Fossey (oddly, I balk at calling these two ‘art’ since they both seem much more important than that), Radiohead’s “In Rainbows” would be less intangible, less unknowably beautiful. A second category follows - that they are almost impossible to accurately review.

To The Wonder ought to be ‘great art’ then. Though every shot is an award-winning photograph, it is not photography. It certainly isn’t philosophy as it is a lot less pointed than that – in other places, Terrence Malick has been described thoroughly unhelpfully as a ‘mystic.’ A novel or a poem would collapse under the strain of revealing the beauty of the natural world as imaginatively yet truthfully as film. To The Wonder makes such excellent use of classic music that it would be less powerful without it, however music alone would not suffice. To The Wonder is essential cinema precisely because it is essential that it be cinema. Similarly, it will lose a lot of its potency off the big screen.

To The Wonder is also nearly impossible to write about, though Nick Pinkerton makes a much better effort at it. To The Wonder defies interpretation since any single meaning that might be uncovered is reductive. Any description of an image and its meaning is only a pale comparison to watching the film itself. It is a difficult watch, but then a lot of ‘great art’ is not something that can be flicked on and passively understood. To The Wonder requires patience and a certain fluidity in the viewer, a willingness to engage with the film sincerely and without embarrassment. Something that would otherwise be mawkish or annoying (like in Malick’s previous, The Tree of Life, there is a lot of dancing) is, in Malick’s cinema, celebratory and free. To The Wonder will not be for everyone, but those who are open to it might find that they come out of the cinema a little different than when they went in. The plot can only be understood by implication just as the film can only be appreciated by thought, the drawing of links with one’s own life and an acknowledgment of its lyrical and visual beauty.

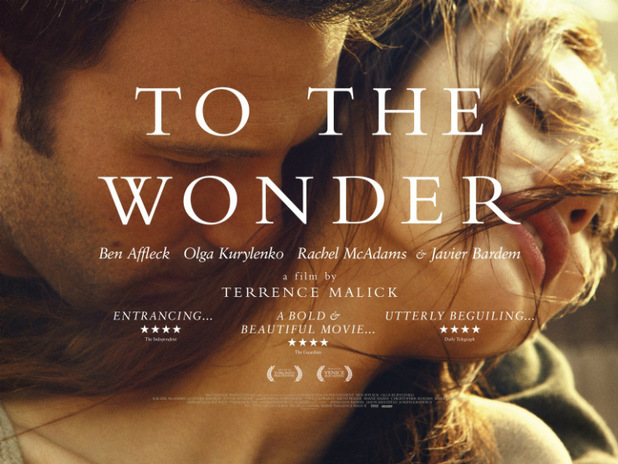

Neil (Ben Affleck) is in a relationship with Marina (Olga Kurylenko). When she returns to France, her home country, Neil gets into a relationship with childhood friend Jane (Rachel McAdams), but when Marina returns, he goes back to her. Meanwhile, Father Quintana (Javier Bardem) struggles with his inability to find God. To The Wonder is most obviously about searching for an understanding of something that is beyond human knowledge. Marina and Jane both try to capture an eternal happiness with a reticent Neil, who comes out of his shell only rarely. Ultimately, they are looking for love, while Father Quintana tries to find proof of God’s existence. This bare plot is then used, by Malick, to explore the world in a way rarely seen. At one point, it feels as if Malick has proved the existence of God by filming sunlight illuminating a garden fence – an entirely personal reading that, very probably, no one will agree with. The characters are ultimately either successful or not, their prize being acceptance. Father Quintana seems to find God or at least to become happy with the search. Marina’s mood varies – she might see a reason for being in an interaction with a flock of migrating birds yet she can still be in the depths of despair in a scenic field surrounded by horses. The return to Mont Saint-Michel, which Neil and Marina visit at the beginning of the film, suggests less a regression or a fondly held memory of better times, but a sign of hope and of constant renewal – Malick presents some beautiful footage of the oncoming tide that surrounds Mont Saint-Michel. The film finishes here, but it is not a conclusion.

To The Wonder is achingly beautiful, embarrassingly unironic and totally sincere. Terrence Malick is a brave filmmaker, because some many people find it too easy to laugh at his films and many more will merely turn away, bored out of their mind. To The Wonder might be his most divisive film, but it is also one of his best. For others, it might take a period of weeks or months before they have totally made their mind up about the film only, I suspect, for a second viewing to open up whole new avenues of thought. For me, since one’s response to Malick’s cinema can only be personal, To The Wonder is a film to cherish and one to watch many, many more times.

No comments:

Post a Comment