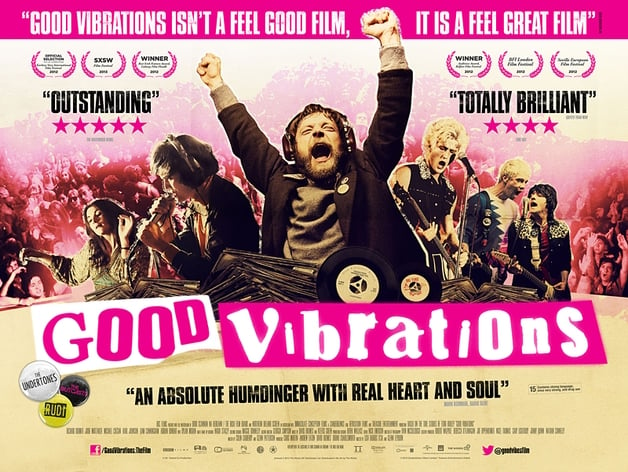

Good Vibrations takes its

name from a record shop opened by Terri Hooley (played here with a lot of charm

by Richard Dormer) on Great Victoria Street at the height of the Troubles –

back when the street was known as “Bomb Alley”, the most bombed half-mile in

Europe. After having an epiphany during a Rudi concert, Hooley starts making

his own records, creating a punk legacy in Belfast, which managed to cross the

sectarian boundaries like nothing else. The key moment, of course, is when he

meets a small band from Derry with a song called “Teenage Kicks.”

Good Vibrations makes it

clear from the very beginning where it stands on the Troubles – horrified

non-participation. Hooley simply ignores it, having fallen out with all his

political friends who have split to join divergent paramilitary groups.

Hooley’s mission is to bring people back together through music – something

that is taken a little too literally in an awkward scene in which Hooley makes

peace with his old friends by handing them a pile of free records – rather than

reach some kind of political or social calm. This is fair enough, obviously,

since the film is more about a man trying to bring punk to Belfast. However,

the film grows entirely unconvincing by its conclusion.

The Belfast Telegraph has declared

that Good Vibrations is the best Northern Irish film ever made. This, I

think, is unfair. Leaving aside the loose definition of what constitutes a

Northern Irish film - since its budget and locations come from both sides of

the border – this declaration gives the film too much praise. It makes the film

appear to be something it isn’t. Surely the “greatest” Northern Irish film ever

made should be more than just a cheeky little pop movie – it should be a film

that says something profound or important about Northern Ireland itself. To

digress briefly, two Irish documentaries produced years ago provide a good

comparative example: one, Mise Eire, celebrated the successful

revolutions that brought independence to most of Ireland; the other, Rocky Road to Dublin, criticized Ireland for its stagnation since

independence, claiming that the legacy of the heroes of the past was just as

guilty as the Catholic Church, lacklustre politicians and rampant state

censorship for a country stuck in the past. Sadly, Good Vibrations is Mise

Eire’s fictional Northern brother, a celebration of a country that is still

broken. With gleeful, optimistic denial, Good Vibrations ends with a

note saying that the Troubles are now over and ignores that Northern Ireland is

still divided and deeply sectarian. The film becomes a

politician-and-tourist-board-friendly film that gives Northern Ireland and its

people, whatever race or creed, the big pat on the back that it does not yet

deserve.

Obviously, it is silly to watch Good

Vibrations and expect a cogent political assessment of the here and now,

but it remains part of an irritating trend in Northern Ireland of celebrating

small achievements and ignoring big failures, of assuming everything is all

right despite today’s widespread protests and the dissident violence that has

not yet gone away.

Having said that, Good

Vibrations is undeniably a feel-good movie. Dormer’s plucky performance – it’s hard to

remember him playing a heavy in last year’s Jump - makes the whole thing

thoroughly likable and the film’s mood, one of sorrow and horror at the

violence and yet retaining a deliberate, almost oppositional, sense of fun, is

recognisable. The sequence in which “Teenage Kicks” is finally

played is note-perfect and almost brings a tear to the eye. The

helicopter-spotlight as super trouper idea makes for one of the movie’s most

memorable moments. Though the directors, Glenn Leyburn and Lisa Barros D’Sa, do

play around with the imagery a little too much, a failing that made their

previous debut feature Cherrybomb such a palpably shallow experience,

they show a real talent in their use of music.

However, the film’s greatest

weakness is a threadbare plot in the film’s second half when things get more

serious and the profane cheerfulness of the humour that is so recognisably

Belfast disappears. The film isn’t consistently funny and yet seems impatient

with the more dramatic moments – Jodie Whittaker, playing Hooley’s wife, has a

non-part that requires her to unsuccessfully try to put manners on Hooley and

then disappear. By the time the film ends with a concert in the Ulster Hall, it

has over-romanticised its subject into fantasy.

Good Vibrations is

a sign that Northern Ireland will begin producing films regularly, rather than

the fits and starts that saw something as great as Peacefire come and

go. Who doesn’t want a healthy domestic cinema and, in time, a masterpiece

even? Good Vibrations is a lot of fun and has two or three rather moving

moments, but it is nonetheless a film that gives a country a pat on the back

when what it really needs is a kick up the arse.

No comments:

Post a Comment