Following the final two Twilight films with a topical, controversial and political film about WikiLeaks –

the first fiction feature about Assange and his whistleblower website – should

seem odd. However, anyone who can make anything halfway conventional out of the

downright bizarre final instalment of the “Twilight” books is a safe pair of

hands, and Bill Condon’s treatment of the WikiLeaks story seems, therefore, to

be more a story of resistance, grey-area ethics and mutual recrimination than

anything particularly polemical or rebellious – though it may work as an

introduction for anyone who prefers their head in the sand.

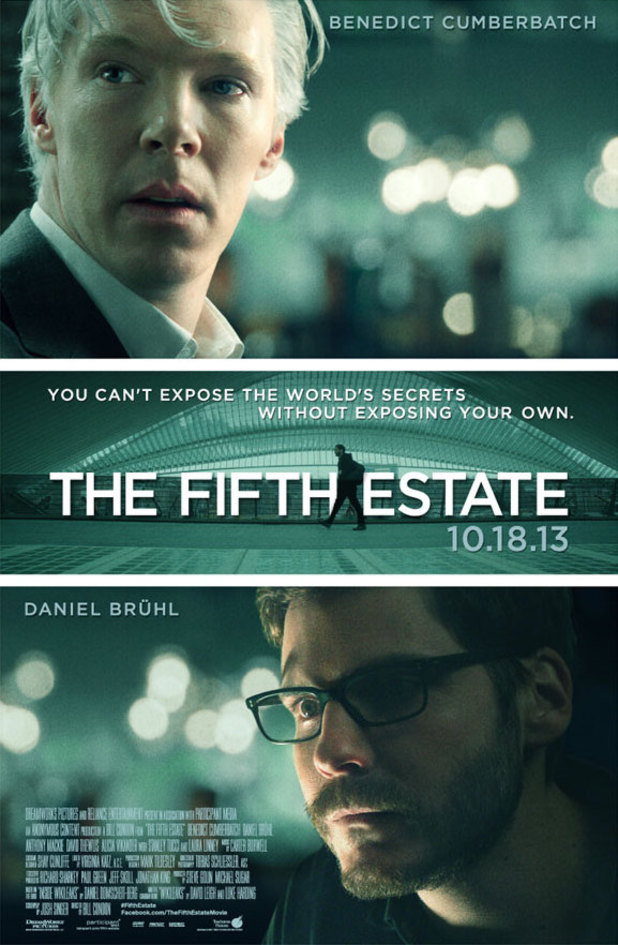

In Berlin in 2007, Julian Assange

(Benedict Cumberbatch), the founder of a small website that offers to publish

whistleblower information with full anonymity for the whistleblower, meets

Daniel Domscheit-Berg (Daniel Brühl) and is almost immediately taken by him.

They dedicate themselves to making WikiLeaks the infamous and influential

website that it would become. However, from the start, Domscheit-Berg is kept

disconcertingly out of the loop. Meanwhile, Assange is moving further and

further into uncharted territory, putting them both in danger.

The film is based partly on the

book, “Inside WikiLeaks: My Time with Julian Assange at the World’s Most

Dangerous Website” by Domscheit-Berg himself. This, and the reticence of

Assange himself, makes the film feel one-sided with a hint of character

assassination. The air of mystery that the film shrouds around Assange hinders

Cumberbatch’s performance – his unknowability and unclear motivations leads to

a vague central performance. Assange is ultimately a figure both heroic and

villainous and a film made with such a Hollywood framework is unable to find

any middle ground. It ends up with two extremes – where one grateful woman

tells Assange that if he had been around during the Cold War the Berlin Wall

would have fallen much sooner while we also see him as working primarily for

himself. The film ends sharply on the latter point, with a line intentionally

comic, but also, in a way, dismissive.

There are a lot of flashbacks and

backstory given concerning Assange, which, given that the film will ultimately

throw up its hands in seeming exasperation at the truth of Assange’s character,

are rather unnecessary. They do not reveal much in particular, leaving a

conventional tale about two friends with big ideas falling out – not unlike,

say, The Social Network, another film with a lot of people looking at

laptop screens though a lot less awkwardly. Condon seems to have attempted to

pre-empt such criticisms with a series of flashy cuts and a dreamscape of The

Crowd-style computers, each an alias for Assange, all utilised in an effort

to explain hacking in what feel like simple terms. Otherwise, the film feels a

little too tightly structured, with the complicated real world story twisted

into a three-act structure, aided and abetted with lines like, “If you are

going to put yourself on a cross, you should first find out what it is made

of.” All of this distracts from the real meat of the story, the central issue

that anything about WikiLeaks must address.

The central issue, and one that

the film takes a long time getting to, is whether or not Assange should have

released Bradley Manning’s leaked files with redactions in order to protect

certain people from reprisals. Fairly conventionally, the film opts for an easy

answer – Yes – with little debate, offering only ethics as the determining

factor. This despite clearly showing the importance of full disclosure elsewhere,

when revealing the vicious murder of civilians in Baghdad and subsequent

cover-up perpetrated by US forces. Although The Fifth Estate does not

choose the wrong answer to the above question, it does nevertheless offer

simplistic, fairly conservative ones. It seemingly suggests that WikiLeaks’

exposures are justified as long as they are not too damaging to the US, that

anything diplomatically survivable is fair game but anything too

horrendous is best left under wraps. In typical Hollywood fashion, a complex

question is represented with a definitive answer, a happy ending of justice

done and full closure – if not full disclosure.

Having said that, The Fifth Estate remains

somewhat nice to see, a further American film showing real world dissent –

Batmanglij’s The East is another recent example. Though neither are

fully committed to anything too radical or risky and both opts for easy

cop-outs, they are nevertheless films that recognise a prevalent villainy

within the American establishment. The Fifth Estate is ultimately too

safe, too apologetic – the sympathetically drawn State Department official

Sarah Shaw’s (Laura Linney) point that “if you don’t want dirty pictures, don’t

have dirty wars” is remarkably feeble since it suggests that the USA is justified

in causing as much ‘collateral’ damage as it wants and, worse still, that the

dirty war was somehow ‘wanted.’ Nevertheless, a wide audience for a film like The

Fifth Estate may be a good thing, especially if it enrages and leads to

further reading. As likely as this may or may not be, the fact remains that, The

Fifth Estate is just not angry enough.

No comments:

Post a Comment