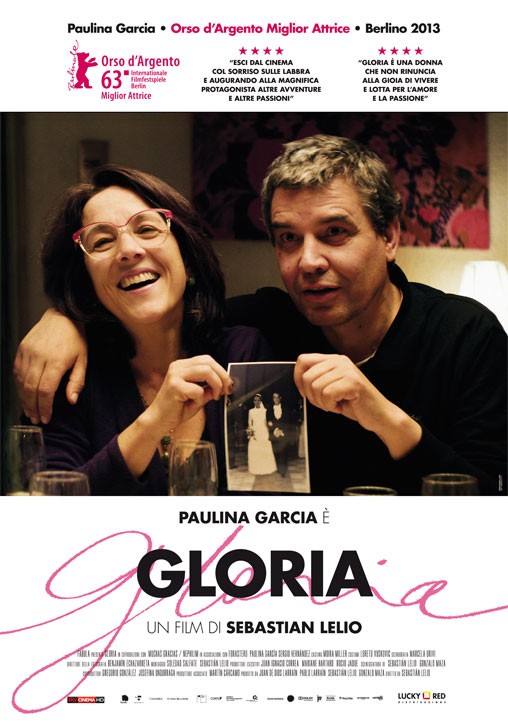

Gloria is a Chilean film

from Sebastián Lelio, with what really ought to be a star making turn from

Paulina Garcia, if foreign language cinema got as much attention as it should.

Gloria (Garcia) is in her late

fifties and is in search of a man. We are introduced to her with long, slow

takes which pick her out of the crowd in a bar in the opening shot and then

follow her throughout the rest of the film. We see everything from her

perspective – from her children who clearly call only rarely to her ex-husband

Gabriel (Alejandro Goic) who is coming to regret his past neglect, to her new

boyfriend Rodolfo (Sergio Hernández, who looks exactly like the late Ben

Gazzara) who is still under the thumb of his ex-wife and layabout daughters.

Over the course of the film, as Gloria and Rodolfo’s romance plays out, we get

to know Gloria, her fragilities and her surprisingly confident manner.

The best thing about Gloria is

Paulina Garcia’s performance, to which Lelio’s camera is largely subservient.

In much worse films, the figure of the middle-aged woman out for love is seen

as either pathetic or horrible. Garcia and Lelio make sure that Gloria is

treated much better than that – they refuse to find anything tragic or funny in

her situation, insisting instead only to document it as realistically and as

truthfully as possible. Indeed, the film is both sad and funny, but all the

best laughs are Gloria’s – we are most definitely laughing with her – and all

the sad moments are truthful and honest, not pitying or patronising. This

respect for a character shines through, giving the audience an equal respect,

and this empathy is ultimately what makes the film such a pleasing and joyful

experience. The film ends on a lovely, cheering moment of self-confidence –

Gloria may not be happy, but she is not letting that stop her from having a

good time. It is a great moment, because we feel that this character has gained

something positive and that she’ll be all right. Acting as the perfect

summation to the film, it is a realistic but heartening ending, where it could

have been cloying and sentimental. It is also helpful that the film does not

have her find happiness in a man instead of in herself – the kind of cop-out

ending that often mars Hollywood films that dare to address these themes, see,

for instance, Bridesmaids.

There is a political edge to the

film as well, in keeping with a strain of recent Chilean films that are

readdressing the country’s history, from Patricio Guzmán’s Nostalgia For The

Light and Pablo Larraín’s Post Mortem and No – Larraín takes

a producer credit here. A slight reference is made to life under the Pinochet

regime and students are marching the streets calling for revolution. Gloria is

made to represent Chile – a dark past, an inner conflict between change and stagnancy

and troubled by despondent youngsters. Initially, when we first meet Gloria’s

son and daughter (Pedro and Ana – played by Diego Fonecilla and Fabiola

Zamora), both are distant and have clearly not called in quite a while. And

yet, as the film moves along, they both appear warmer to her, as if a change in

her has facilitated an improvement in their relations. Meanwhile, Rodolfo’s

kids remain dependent on him and his inability to break these bonds is

ultimately his major failure. While the politics is there, it is dealt with

quietly and it is far from the film’s raison d’etre.

As well as that, Garcia and Lelio

(and, to a lesser extent, Hernández) challenge the traditional sex scene, which

is usually exclusive to the young and slim. Gloria features sex scenes

between two middle-aged people that are surprisingly explicit and yet are too

rarely seen in other cinema. It is an honest depiction and one that counters

ageism to offer a more democratic way of looking at sex in films. Though some

may find them a touch out of place (as they are in Blue is the Warmest Colour), it remains an example of a daring film that is not afraid to take

risks and challenge common prejudices, representing unintentionally the need

for a vibrant art cinema to oppose an increasingly conservative Hollywood.

Gloria then

strikes a blow for a more honest representation of age on screen. As worthy of

praise as it is, it is, nevertheless, fundamentally a charming and pleasing

film about a woman looking for love with a perfect, uplifting ending. Paulina

Garcia holds the film together with a daring, powerfully empathetic performance

while Lelio displays a great ability to capture moments of truth – particularly

in a birthday scene in which all of the major characters are present, one that is

full of nuances, significant glances and pregnant silences. Lelio is definitely

one to watch but then so is Garcia; their collaboration being so significant

that it is hard to separate their work for individual praise. However it is, Gloria

remains a fantastic achievement.

No comments:

Post a Comment