Bruno Dumont is an auteur in a

rather extreme sense of the word. While his films are imbued with a developing

style that is all his own and with consistent themes, unfamiliarity with his

early work may make it harder to fully appreciate his later work. Having seen

only last year’s Hors Satan (apparently the endpoint of what was then

his stylistic concerns) before seeing Camille Claudel 1915, it is hard

not to imagine that one is missing something which will only make sense when

one has seen how this filmmaker’s ideas have developed from his debut – La

vie de Jésus – onwards. One consistent thing between the two I have seen,

however, is the Pasolini-like concern with how religion and reality coincide.

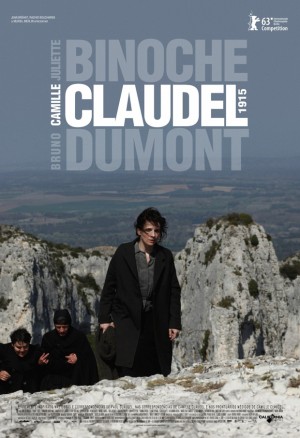

Camille Claudel 1915 is a

very specific title for a rather specific film. The film largely follows a

typical section in the life of sculptress Camille Claudel (Juliette Binoche),

who has been placed in Montdevergues Asylum. In her second year at the asylum,

Claudel is clearly unhappy, suspicious of the motives of the nuns who care for

her and feeling abandoned and imprisoned. Her existence is severely limited and

depressing. Her one hope is her brother Paul (Jean-Luc Vincent) who is coming

to visit her shortly.

The film is very minimalist –

even more so than Hors Satan – focussing almost exclusively on Juliette

Binoche’s face in close-up. As a showcase of Binoche’s talents, it is possibly

unparalleled since the film spends a lot of time on Binoche’s face as she

silently conveys Claudel’s inner turmoil with limited dialogue. The first hour

of the film starkly represents Claudel’s life in the asylum, living amongst

mentally disabled adults, all of whom were played by genuinely disabled

non-professional actors (the nuns were also non-professional actors and professional

nurses), cooking her own food, writing letters to people she thinks may help

her, praying and just simply sitting and looking around her. The film offers a

long hard look at one woman’s imprisonment.

Where the film most clearly

represented Dumont’s concerns about the meeting of the sacred and the profane

is in the scenes towards the end of the film involving Camille’s brother Paul,

a deeply religious and incredibly self-righteous man whose strong beliefs are

effectively imprisoning Camille since his refusal to release her is based on

his beliefs. Their long-awaited confrontation at the end of the film only

represented her entrapment of the more since their conversation is stilted and

uncommunicative. Camille complains of her imprisonment and vents furiously

about the men she thinks put her there (her former lover Rodin whom she hasn’t

seen in twenty years) while Paul can only look on and shake his head.

Another instance in which the spiritual is checked or

forced into contrast with reality is in the faces of the other asylum inmates.

Dumont trains his camera on their faces – which may or may not feel

exploitative depending on one’s point of view – representing either the

religious clichés of the holy fool or an instance in which religion is not

present and cannot help. In one scene, a nun helped a patient into the church

despite the fact that his feet hurt and he has no idea what God or heaven is.

The contrast is presumably intended to be similar to that in Pasolini’s Accattone

in which a street fight is famously and rather movingly scored with sacred

music by Bach.

If the film feels then like a rather slight work, it is

because the film intends to be an accurate representation of what Camille

Claudel’s life must have been like in 1915, hence the specific title. Two years

into an imprisonment that would last almost thirty years until her death – as

one incredibly stark note states at the end of the film – we see a Camille that

hasn’t yet given up hope, one that still expected to be allowed out of her asylum.

That said, and after only one viewing, it seems that

the film may have more to it than simply a representation of imprisonment and a

vague interest in the clash between religion and reality. Like Hors Satan,

which imagines what a modern day, country-based Jesus or Satan would be like, Camille

Claudel 1915 feels like a film that will reveal more with further viewing

and a deeper familiarity with the filmmaker’s work. No bad thing, but it means

that some further study is required.

A shorter review is available here.

No comments:

Post a Comment