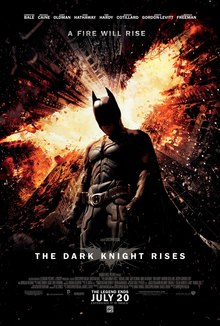

With The Dark Knight Rises, Christopher Nolan apparently closes his retrospectively named Batman trilogy. Nolan has long been credited with making intelligent blockbusters that engage the mind as well as delivering all the thrills and spectacle that the Hollywood big budget production line demands. With The Dark Knight and Inception, Nolan has managed to create blockbusters that are oftentimes complex and open to many interpretations. Does his fondness for clever action spectacle shine through in The Dark Knight Rises?

Eight years after the events of The Dark Knight, Bruce Wayne (Christian Bale) has become a Howard Hughes-like recluse. Older and frailer, he has left Gotham City to the care of the police. However, Commissioner Gordon accidentally discovers an underground army, run by Bane (Tom Hardy), which threatens to rise and attack the very fabric of Gotham’s existence.

Initially, the film is a bit of a mess, hurriedly introducing several new characters, who will all become important later, with several different plot threads which will all tie up in some unlikely ways. The film is slow to find its footing and it is frequently wrong footed as the convoluted plot carries on, making varying degrees of sense as it goes. Rarely does the film manage to find a key scene and stick with it, with several scenes that should be have much more significance being lost in a fast-paced montage of several, much more functional scenes. Even key emotional scenes, like those between Wayne and his butler Alfred (Michael Caine) appear rushed, intended to important context or motivation, disappear from the screen and, often, from memory much too quickly. The film is rarely allowed to breathe and never really recovers from its rushed and often rather hackneyed pacing and storyline, becoming, in the final analysis, a film without a core.

Much less comprehensible is the film’s final point. Critics, in particular, pride themselves in identifying Nolan as a blockbuster director with smarts, but The Dark Knight Rises is a shallow film. Yes, it references the economic downturn and the culpability of the rich, but they are exactly that – references without any real conclusions being drawn. The same can be said for the film’s politics. One of the more difficult things about The Dark Knight was an ending that advocates lying to the public in order to get the job done, epitomized in this film with the Dent Act. Put simply, Batman and Gordon are lying to the people of Gotham City for their own well-being, a difficult proposition not so long after the WMD controversy. The Dark Knight Rises does ultimately disown the previous film’s conclusion and the Dent Act, but instead it starts talking about the people. Batman frequently talks about the importance of the Batman as a symbol for the downtrodden and about what he must give to the people of Gotham (a typical exchange being – Catwoman: “You don’t owe these people anymore. You’ve given them everything?” Batman: “Not everything. Not yet”; an apparent suggestion that he can still give his life). Similarly, Bane preaches to these same people that Gotham City is theirs for the taking and that they must fulfil their own destiny, one without the lies and falsehoods of Batman and Gordon and the Dent Act. However, where are these people of Gotham and who are they? We never see them (even when Bane’s minions attack innocent people, they are clearly the rich and privileged) and when Bane takes control of Gotham, are we to assume that the people are all collaborators? We never see them rebel against Bane, like the police ultimately do. And if they have joined Bane, then why is it so important for Batman to save them? In fact, the only so-called people of Gotham that we see are two construction workers who are openly colluding with Bane. There is a message somewhere in The Dark Knight Rises, one that is ultimately a humanist one about the importance of looking after each other and helping people in need (this does come across towards the end in a clipped conversation between Batman and Gordon), but it is lost in the flow of (too much) information and by the typically Hollywood need to move along quickly to the next money shot or action sequence. Nolan might be credited with pioneering the clever blockbuster lately, but with The Dark Knight Rises, he has made a rather facile action film that superficially presents real-world problems and fails to cohere around any central point.

When it wasn’t being silly, The Dark Knight proved surprisingly adept at being exciting. Aside from many well-constructed action sequences, the film was an often stirring and fascinating examination of terrorism, psychosis and widespread hysteria with many scenes that matched the sweep of Michael Mann’s classic Heat with a complexity and intensity that seemed to defy conventional blockbuster rules. The Dark Knight Rises is clearly aware of what made The Dark Knight’s best scenes work so well, but it has given itself too little space to successfully replicate them, with even the film’s action scenes paling in comparison. However, the film is not a total write-off. After all, the performances are still of a high standard, particularly, as with the two previous films, Gary Oldman, the direction is broad and interesting and the cinematography is flawless. But it smacks hopelessly of expectations not met and of the bar having been raised too high.

The Dark Knight Rises is a messy film that could have used a tighter, tougher script and more consideration as to what the film is supposed to be about. The typical Nolan ambiguous ending really should have worked but feels botched, if only because certain revelations make Batman’s actions seem odd. The film fails ultimately to measure up to The Dark Knight, a film whose flaws were outnumbered by its graces. With too few graces to make it work, The Dark Knight Rises is ultimately beaten down by its flaws, which are often too big to ignore.

No comments:

Post a Comment