In 1965, a military coup crippled

Indonesia. Begun apparently to thwart a communist coup in October, the

military, under General Suharto, slaughtered half a million people with the

active support of both the USA and the UK. Suharto violently suppressed all

opposition and led a corrupt government. Thatcher visited in 1985, later

writing in “The Downing Street Years”, “though there have been serious human

rights abuses, particularly in East Timor, this is a society which by most

criteria ‘works.’” This was Indonesia’s invasion and occupation of East Timor

between 1975 and 1999, which killed a further one hundred thousand people.

Since a society ‘works’ despite human rights abuses, Callaghan, Thatcher and

others continued to sell Suharto arms. The murderers in Indonesia live on with

impunity and they are still in power – still able to intimidate their

neighbours and still honoured on national television for crushing the

communists. Essentially, they are mass murderers who won, their crimes ignored

(two and a half million killed) and their country running along thanks to the

support of the capitalist West.

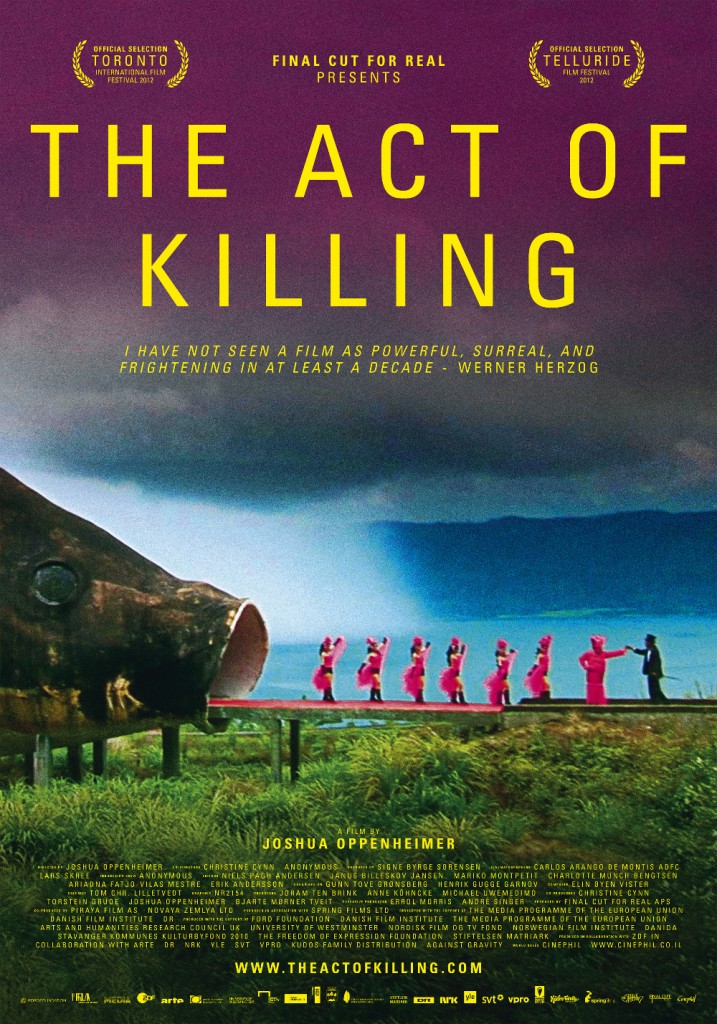

The Act of Killing follows

a number of these murderers, particularly Anwar Congo, a self-proclaimed

gangster and sadistic murderer, who looks back on his crimes with pride and

nostalgia. They were leaders of their local Pancasila Youth paramilitary death

squad. Initially, we see Congo and his old colleagues describe their killings

and their love of cinema. These two interests go uncomfortably hand-in-hand

when Congo describes going to see an Elvis film and then swaggering across the

road to kill more prisoners. The documentary follows them as they attempt to

recreate their tortures and killings, turning genocide into spectacle, offering

insights into their thoughts and motivations.

The film’s main novelty is the

fact that it contains interviews with wholly unrepentant murderers and a lot of

the most shocking scenes are both evil and banal. These people make jokes about

their murderers (one recounts an incident wherein he walked down a street,

stabbing any Chinese person he found and he is sure to finish with a punch

line) and are frequently honoured as war heroes and patriots. In a break during

filming, one killer boasts of how many women he used to rape during a raid of a

village and, in particular, his pursuit of fourteen-year olds to a group of

laughing cohorts. However, as the film progresses and the re-enactments,

ranging from gangster movie pastiches to musical numbers, continue, the façade

cracks and some of the murderers, particularly Congo, begin to express regrets.

This is not to say that the film

lacks contemporary insight since many of these ‘gangsters’ – frequently

translated as ‘free men’ – are still active. One even stands for election into

a corrupt government. We see them travelling through their neighbourhoods,

extorting money from local businesses and forcing mostly quiet and distant

people, for fear of showing disobedience, into participating in their epic,

violent visions. One actor reveals himself to be a child of one of the murdered

and yet participates nonetheless. These scenes are disturbing and enraging and

they also point to the ongoing lack of justice in Indonesia, but they are also

part of where The Act of Killing falters.

The film is very short on

context. The text at the opening of the film is brief and not very detailed. It

is also unclear whether director Joshua Oppenheimer initiated the project of

re-enactments or whether he is merely following a pre-existing phenomenon. As a

result, we are given very little insight into Oppenheimer’s dealing with these

people and, hence, his own culpability with the evil we see and hear. Congo and

his friends are clearly acting for Oppenheimer’s camera but what about the

local people and the business owners who are filmed being threatened. Is

Oppenheimer’s camera observing or instigating? When we see neighbourhood

children (with, very possibly, relatives who are/were victimised by the

Pancasila Youth) crying, clearly disturbed by the violent nature of the

re-enactments that are being filmed, may our own outrage not justifiably be

directed at Oppenheimer for encouraging Congo et al.?

Similarly, there are too many

scenes that feel a little too convenient. At the film’s end, Congo, having

shown a re-enactment of one of his tortures to his grandchildren, suddenly

starts to show real remorse. He says that he now understands how the victims

were feeling since he had the same feelings during the filming. Now, and only

now does Oppenheimer challenge him – saying that it is incomparable since Congo

was being tortured for film and his victims were being tortured for real. Then,

we cut back to the rooftop were Congo strangled so many of his victims to re-do

a too-light hearted previous demonstration of his methods. Suddenly, Congo

seems to be violently, physically suffering from the enormity of his guilt,

loudly retching and visibly shaken. This sequencing is unexpectedly moving and

offers a harrowing reminder that these mass murderers are not, after all,

monsters. However, since Oppenheimer hides the nature of the documentary’s

production, these scenes feel manipulated and deeply untrustworthy. Conclusions

are too easily drawn and their honesty and ultimate truth is difficult to come

by. It is not clear if we are seeing everything and if the editing choices were

made in the pursuit of verisimilitude or merely a good story and drama.

The Act of Killing is

valuable in demonstrating what Indonesia is today but also the kind of state

that the West is prepared to support for their own economic interests. It is

valuable for its undeniably real scenes – such as the talk show honouring the

murderers broadcast on national Indonesian television and interrupted by

frequent applause from the audience for each barbarity mentioned, a clip that

really has to be seen to be believed. It is awkward formally and depends on

withholding, manipulation and subterfuge much more than is comfortable. Its key

message is damaged thanks to its untrustworthy and unsophisticated

presentation. However, this message, either explicit or implicit, of full

impunity for murderers in Indonesia and of the West’s culpability in mass

slaughter, is worth telling again and again.

See also: Into The Abyss: A Tale of Life, A Tale of Death (2012)

No comments:

Post a Comment