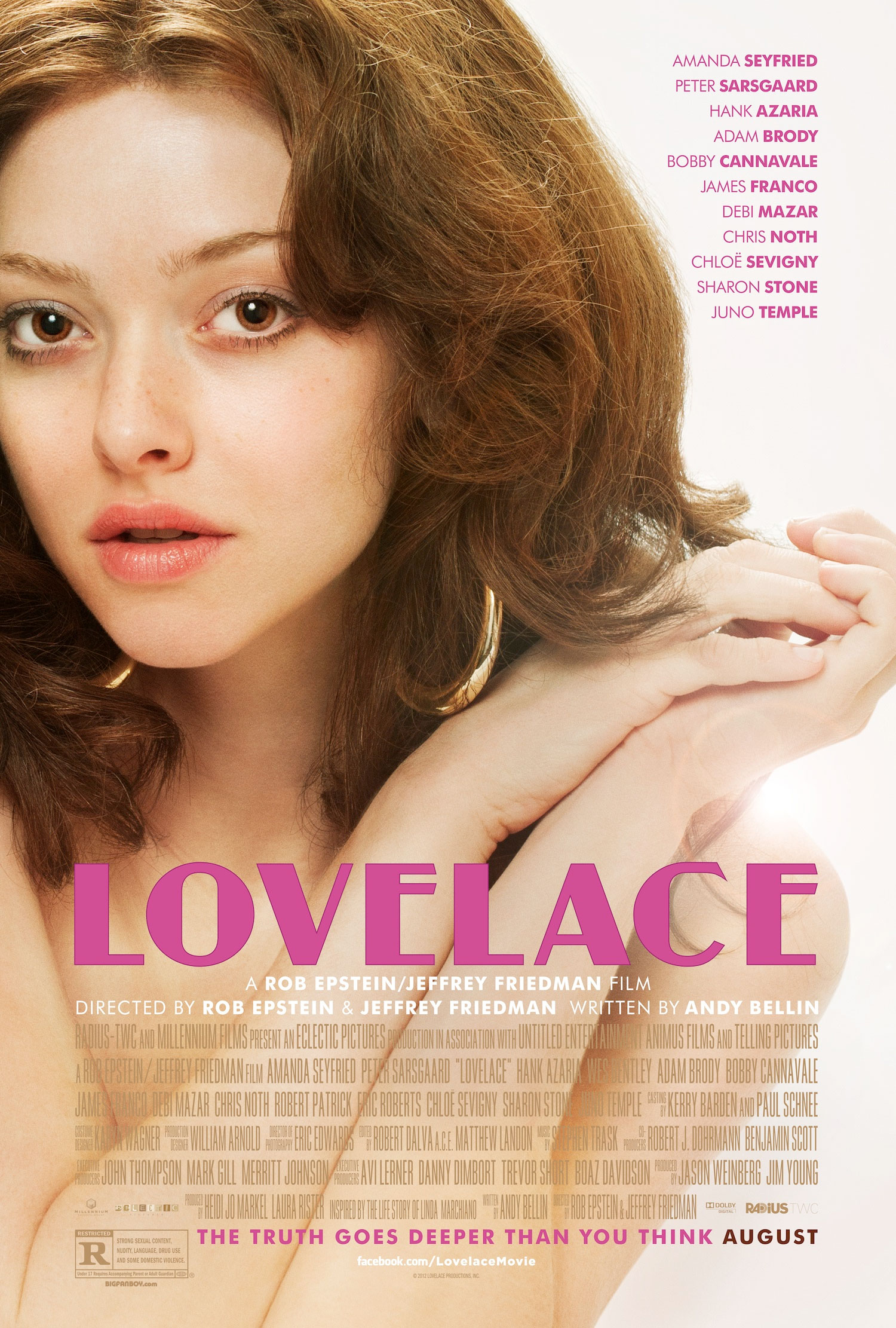

In 2010, Rob Epstein and Jeffrey

Friedman directed Howl, a biopic/documentary/animation about Allen

Ginsberg and his controversial poem “Howl.” Lovelace is a similar

attempt to look at the history of America’s sexual liberation, focusing on

another controversial figure and another work that was tried for obscenity.

The common conception of Deep

Throat, probably still the highest grossing pornographic film ever made,

was that it ushered in a certain respectability for the porno and made it’s

lead, Linda Lovelace (played here by Amanda Seyfried) the first porn star to

make it as a star. It struck a blow for the sexual revolution and was exhibited

far beyond the dank fleapits that usually played pornography. However, the

reputation of the film has been subsequently tarnished. Lovelace spoke out

against the film, claiming she was coerced into making the film by her violent

then husband Chuck Traynor (Peter Sarsgaard). She has said that to watch Deep

Throat is to commit rape. Epstein and Friedman’s film takes an interesting

approach to showing this dual conception of Lovelace and Deep Throat.

The first half of the film is a

primarily rosy-eyed look at the making of Deep Throat and Lovelace’s

subsequent stardom. It is a typical tale of a girl leaving home and growing up,

the porn angle only adding to the transgressions. It feels like an Apatow film,

filled with jokes about blowjobs and even James Franco as Hugh Hefner. It is

uncomfortably light, almost offensively so, especially if you know about

Lovelace’s later comments. However, halfway through, when Lovelace’s star is at

its highest, the film rewinds back to the beginning and repeats some of the

same scenes but this time makes their sinister side clear. Traynor moves from

being a happy-go-lucky charmer who can get a bit angry to being an unrepentant

psychopath, constantly beating Lovelace up and forcing her into worse and worse

situations. Oftentimes, scenes that were played for laughs earlier become much

more ominous. This strategy reveals the two sides to the Lovelace story, but it

is somewhat diminishing, where a scene that should be horrible is less so since

it plays out as part of a temporal trick. The other odd thing about it is that

while certain moments within the film’s first half are corrected by the second

half, its overall feel is allowed to stand.

Lovelace would later campaign

against pornography as well as for women’s rights, but Lovelace seems to

let the pornography industry off the hook. Instead of viewing what happens to

Lovelace as an inevitable product of this highly exploitative industry, the

film instead offers up two simple hate figures. Chuck Traynor is portrayed as a

full-on psychopath and is clearly the villain of the piece, but by emphasising

his evilness the film allows the pornography industry to dodge any culpability.

‘The pornography industry has its psychopaths, just like anywhere else. Let’s

just leave it at that,’ the film seems to be suggesting. The pornographers are

presented as misogynistic, but only in the sense that they are out of time – as

if misogyny is, like the carefully chosen costumes and the big hair, a thing of

the past. Misogyny isn’t shown to be endemic within this industry, more a

by-product of the ‘70s than of pornography. Similarly, the pornographers are

allowed to remain innocent. Although they all profit massively from Lovelace’s

exploitation, they are allowed a degree of deniability as if Lovelace’s life

off the set is no concern of theirs. And while the second half of the film

delves back into the first half, unpicking sinister undertones that you might

have missed, it never shows us the dark side of the makers of Deep Throat,

that they knew about what was happening but didn’t care to disrupt their

production. Hence, the film is not as radical a critique of those that Lovelace

herself has made, giving it the feel of a film that shows horrible things but

then tries to make excuses for them.

So the film suggests that

Lovelace’s ordeal has something to do with shacking up with a psychopath and

nothing to do with the pornography industry. The second hate figure is

Lovelace’s mother, Dorothy Boreman (Sharon Stone), who is represented as

disproportionately abusive and uncaring. She actively keeps Lovelace and

Traynor together, refusing to give her daughter her room back so that she can

get away from her violent husband. Meanwhile, Lovelace’s father (Robert

Patrick) is presented as very caring and given a very touching moment during a

phone call with Lovelace. He is gifted with a degree of deniability and, much

like the pornographers, is let off the hook.

Lovelace is well made and

very well acted, particularly by Seyfried, Sarsgaard and Patrick but it is a

slightly uncomfortable film. It is not clear quite why the film avoids

targeting the pornography industry or patriarchy or just misogyny, instead inoffensively

stopping at the two most recognisable villains in American cinema – the

psychopath and the middle-aged woman. No matter what the facts were, and the

facts are unclear enough, it is clear that Lovelace was brutally abused and

that the pornography industry and the society’s sexism were responsible for

allowing it to happen. That the film feels the need to pull its punches here

after such damning representations of individual villains Traynor and Dorothy

Boreman seems to suggest that today’s view of pornography and misogyny remains

stuck in the rose-tinted view of the ‘70s, and this film’s first half.

When you consider the film’s silence on this point

together with Lovelace’s view that to watch Deep Throat is to commit

rape or that Deep Throat itself is nothing more than a filmed rape, it

seems to suggest only that the film is somewhat cowardly. It could have taken a

stand – and it has the perfect horror story with which to do so – but it would

rather play it safe. Pornography isn’t frowned on to the extent that it used to

be and it still hasn’t lost that sexual liberation tag but does that mean that

we should be blind to its very real faults?

See also:

No comments:

Post a Comment